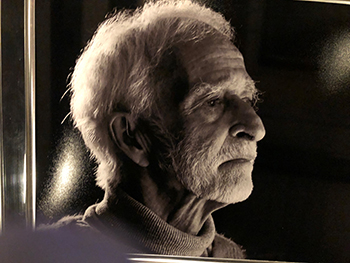

Dr Harry Freeman reflects on his long career.

In the 1970s my first year training in psychiatry was in a huge mental hospital in country New South Wales - there were ten such hospitals, all about 100 years old - sandstone, farm self-supporting, beautiful gardens - run by the nurses and only a couple of doctors.

A hospital house for working wife and baby (and Grandma), pay rise from $4,000 per annum as a similar RMO to $7000 as a registrar, ignorant, grandiose, political activist, anti-Vietnam, anti dominant paradigm, cocktail pianist, energetic and not hesitating. I felt good.

The hospital had four groups of patients, men and women in separate wards. So, as well as the mentally ill, there were alcoholics, dementia patients and those with intellectual and behavioural problems. Each group comprised about a quarter of the hospital population.

These latter groups filled the state’s hospitals by the 1960s. Families no longer able to manage such people as the family dispersed and changed.

Despite more buildings, the hospitals were deteriorating, overcrowded and a Royal Commission in the 1950s determined that they shouldn’t survive. A political and financial decision was made to do psychiatry in the community and in ordinary hospitals.

Creating so-called community mental health is a nonsense, given how many different sorts of humans there are in the communities within which we exist.

The dementia cases would be solved by creating subsidised and non-government nursing homes (predictably seriously problematic), the alcoholics got a few name changes and little else, and the handicap group are doing pretty well in “the community”. The mentally ill are homeless and the drugs which help them in hospital didn’t really solve their problems when out of it.

That is now, but in the 1970s, only 50 years ago, we still had the “mental hospitals”, and I threw myself into seeing all the sorts of souls living there, with little supervision and lots of initiative and hope. I had a great year.

However the permanent staff were caring for patients who were very troubled by unmanageable moods and thoughts, despite treatment, rarely cured; many were troublesome, and many staff were quite demoralized.

I had particular responsibility for the dementia wards (there were few nursing homes then) and extended families were disappearing fast (so no carers for the elderly).

My job was to sign the death certificates (life expectancy was about two years from admission), review/increase medication, do physicals and keep a low profile. Nurses had run the place for the last 100 years.

These patients were in huge Nightingale wards, 50 each, 50 chairs around the day room; chairs with arms allowing a long sheet to be passed along them to restrain the patients, and another long sheet was under the chairs for ...

They were placed in these chairs for breakfast and spent the entire day there, usually needing help to feed (this being the result of the immobilization), doses of sedatives they required for sleeping, usually manacled, with little touch or conversation during the day, and then to bed.

An event I especially treasure was when I was holding an “existential group” in a chronic general ward of mostly mute, occasionally catatonic, paranoid cases when one of them who worked in the farm’s piggery and who had not spoken for 15 years, grunted, during a silence, “But they’re very good to the pigs”. Then he stopped speaking again.

Another memory is of the med super dressing me down for seeing patients in their homes, keeping them out of hospital and discharging too many. This meant he was about to lose a cook because of dropping bed numbers, and in a country town an employed cook is much more valuable than a young doctor!

What did the social reformer, humanist, medico do about this situation where things were obviously seriously problematic? Absolutely nothing. I didn’t notice what was happening, as my education, hard work, political activities and my family were more important. My capacity for selective neglect of major bits of my world, like for most of us, most of our lives, is infinite! Sadly the powerful and influential are similarly afflicted.

For the next four years I was training back in Sydney in a teaching hospital with all types of psychiatric patients, inspiring teachers and staff psychiatrists.

New initiatives appeared like rehabilitation, group work, behaviour therapies, outpatient clinics and Medicare-subsidised “private practice”.

“Mental health” became a well-used term, despite us humans being unique, and what is healthy in some cultures may not be in others. However, mental illness is much the same everywhere in my experience, having worked here and overseas.

In 1974, qualified and having revelled in the Aquarius festival - sex and drugs and rock and roll - I joined my dear friend Igor Petroff who created the Lismore psychiatric service. We worked the area, doing clinics in Tweed, Grafton (including the infamous prison), Ballina, Casino, Murwillumbah and Lismore community mental health clinic. I was Robin to his Batman.

The 30-bed Richmond Clinic (there was only one psychiatric unit between Newcastle and Brisbane) took all sorts of patients who had previously been in the old mental hospitals.

Igor was permanently on call and was a good leader. The new team did much good and up-to-date work, and had excellent morale.

As the area’s population expanded other units opened in Coffs Harbour, Tweed Heads, Kempsey and Byron Bay, with outpatient clinics and no more patients in mental hospitals.

The Richmond Clinic, slowly moving to the back of Lismore Base Hospital, now has wards for adolescents and older folk, but importantly men and women were still in the same wards, which is totally inappropriate.

The wards are as full as available staff allow, but recruitment is hard as the work can be challenging and sometimes quite dangerous.

There is little of the “asylum” In hospital psychiatry now as we oversell ourselves as being able to solve the problems of a rapidly changing society, where the problem of the dissolving extended family manifests, with our selling it with a “we’ll fix it with mental health” or a call to Lifeline.

I’m ashamed that we are shunning public work, condoning a situation where the government is fixing problems by involving NGOs and pretending that the evident upsets so many folk are experiencing can be solved by fixing our individual mental health rather than addressing inequality, unfairness, loneliness, greed and anger, and “me rather than us”.

Our drugs are little more effective than they were 50 years ago, though with fewer side effects. Big Pharma is a serious problem, investing less and less on drugs relevant to psychiatry. However, in truth there is a real problem with creating drugs that do affect our mental life predictably, since it is an amazing thing and care is needed.

We should be as worried about the legal drugs as about the illegal ones.

After 50 years I still have a love for psychiatry and I’m just as curious and puzzled by it as ever I was. I prescribe less, talk less, recognising that the most important therapeutic ingredient is creating a non-judgemental atmosphere in the consultation.

The odd grunt, if only as brief as the comment issued by the piggery assistant long ago, can be terribly important, not least to put a lie to those words penned by George Orwell - four legs good, two legs bad. The welfare of human beings must be at the forefront of all our work.