The federal government has begun placing greater demands on GPs and allied health professionals to help job seekers who have disability, injury or other health conditions to gain employment. Similar pressure is both being applied to individuals affected, while incentives are being provided to employment agencies for these clients to engage in paid work rather than continuing to receive payments through Newstart, Youth Allowance, disability support pensions or parenting support schemes.

However, it is yet to made clear just what role primary care providers are expected to play in the complex job search process.

Disability Employment Services (DES) and Disability Management Services (DMS) are currently being contracted to employment organisations by Centrelink, Department of Human Services.

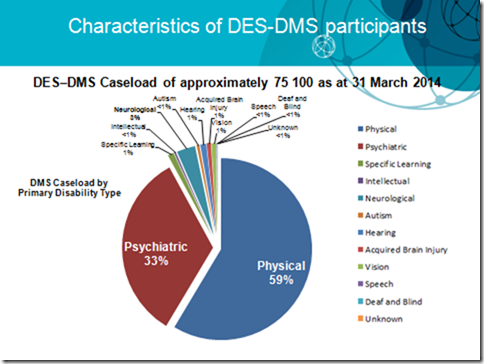

More than 75,000 people are currently participating in DES–DMS. As can be seen in the chart, 59 per cent of the participants currently have physical disabilities, and 33 per cent have psychiatric disorders. All conditions on the chart are highly likely to bring these job seekers into contact with GPs who will often need to refer them on to allied health colleagues for further assistance to manage their health issue.

These clients will invariably need a Centrelink certificate from the GP, with Centrelink then referring them to one of the contracted employment agencies in the area. GPs may already be noticing an increasing number of referrals from these agencies following implementation of the new Government changes to the employment industry announced in the last Budget.

It is not only the employment agencies that are expanding. There seems to be a whole new health industry developing around the need for primary care workers to play a crucial role in the often complex process of helping these job seekers gain employment. Despite this, there does not seem have been much talk or education to prepare GPs for this responsibility. No doubt it is assumed that they are already adept at this type of work.

My personal experience in this area is that many of these job seekers have not had much access to GPs in the past. Indeed, there seems to be a whole new cohort of people coming to see a GP after being referred by an employment agency. The ability and willingness of GPs to take on these cases is likely to vary considerably.

People with psychiatric illness often come from a background where there has been post traumatic stress from childhood onwards due to domestic violence, physical, verbal or sexual assault, alcohol and substance abuse and related social problems.

Many come from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, are homeless, perhaps ex-offenders, while many are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Age groups vary from the younger, who have never had previous employment, to older people who have lost their job and/or fallen upon hard times for whatever reason.

Although this caseload is challenging work for the primary health team it can have its rewards when a needy person progresses and gains employment. Time will tell how successful these new measures are. Job creation and availability will limit what is possible in each region.

At a time of business pressures and rising unemployment there must be real concerns about what solutions will be possible.