A key determinant of health status for Australia’s Indigenous peoples, as Professor Bob Morgan explains.

Australia may be envied abroad for its material riches but most Aboriginal people continue to struggle to overcome the ravages of poverty, the contamination of our cultures and traditions, the impacts of dispossession, the alarmingly disproportionate levels of incarceration and the effects of racism and socio-political alienation.

All of these elements are determinants that help to understand the debilitating health status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

In Viktor Frankl’s seminal book Man's Search for Meaning (1938) on the theory of Logotheraphy, based on his observations from his time in German concentration camps, he argued that, “The human being is an entity that consists of a body (soma), mind (psyche), and spirit (noos).” He explained that we have a body and mind, but the spirit is what we are, our essence. Note that Frankl's theory was not based on religion or theology, but often had parallels to these.

In an Aboriginal context I maintain that Aboriginal people suffer a form of what I refer to as ‘Spiritual Fatigue’, a debilitating consequence of having to either constantly struggle for human rights and freedoms or being forced to constantly defend them. There is no room for celebration and meaning in this paradigm - it is simply a choice between struggle or defence.

Spiritual fatigue aligns with Frankl’s theory of Logotherapy but it is more profound than that. This is due in part because Aboriginal people continue to suffer transgenerational trauma that forces them to deal with a number of effects resulting from being disconnected, and in some cases forcibly removed from Country, some of which holds important and sacred meaning that has been developed over a thousand generations. It is also important to understand that when Aboriginal people speak of Country this extends beyond mere notions of geography.

Added to this is the destruction of Aboriginal languages, the contamination and/or erosion of culture and traditional values, the destruction of age-old lores that have governed and regulated how Aboriginal people lived with each other and with the environment and other forms of life. It involves a loss of purpose and meaning, all of which can be traced to various public policy and social attitudes, the net result is the health disparities, the social inequalities and political marginalisation that defines the life of Aboriginal people in 21st Australian society.

The current alarming rates of Aboriginal incarceration, often the consequence of poverty and cultural erosion, the appalling health inequalities, the ongoing failure of the Closing the Gap (CTG) strategy and numerous other indicators point to the need for a radical resetting of the way that Aboriginal needs and aspirations are identified and responded to.

Increasing evidence-based research illustrates that the greater the involvement of Aboriginal people the more connected to Country they are, the greater the opportunity there is for the practice of lore and the reimagining of purpose and meaning.

We must ask ourselves why non-Aboriginal Australia and our political leaders remain unable, or unwilling, to accept this essential truth. They appear to be wedded to another truth, a form of collective cognitive dissonance… and so the suffering continues.

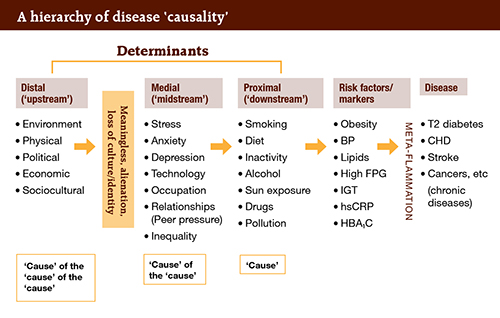

A Hierarchy of Disease Causality

When considering chronic disease patterns, Professor Garry Egger explains: ‘It’s a mistake to think that there is a single cause of chronic disease. Instead there’s a ‘hierarchy of causality’. This is shown above:

- First there is the disease (short list shown here)

- Then there are ‘risk factors’ or markers for these diseases

- But there are a range of ‘determinants’ (not really ‘causes’ in chronic disease)

- First, there are the ‘proximal’ (downstream) risk factors, which are closest to the disease (this is one ‘cause’)

- But there are ‘causes’ of these and they are ‘medial’ or midstream,

- But these also have ‘causes’ and these are called ‘distal’ or the ‘cause of the cause of the cause’). And this is where most analysis usually ends,

- But somewhere between the distal and other levels of causality are the psychological factors that are important for displaced societies.

- These are meaningless, alienation and loss of culture and identity, which are profound for Indigenous cultures.

CTG – a failed Public Health policy

When viewed through the prism of Aboriginal experience, the notion of ‘closing the gap’ implies, perhaps unintentionally, that the underlying causes of the devastating health conditions experienced by most Aboriginal peoples are mirrored in non-Aboriginal society, and therefore Aboriginal inequalities will be best addressed if health systems and providers simply focus on ‘the gap’. This ignores the many factors that underpin the burden of poor Aboriginal health.

These factors include the burden and the nature and scope of dispossession, the contamination of cultures and government sanctioned attempts of genocide, entrenched poverty, racism and the ongoing denial of the fundamental and unique rights and freedoms of Aboriginal peoples in Australia.

Clearly the current strategy is not working, suggesting that a new policy approach should be adopted. Such an approach should be designed to develop effective and empowering negotiated partnerships with Aboriginal people, particularly at the local community level.

Incorporated into any new policy approach should be targets for truth telling and social and restorative justice.

Increasingly research is telling us something that Aboriginal peoples have always known: it is only when Aboriginal people are in control of their own lives do we witness a real shift in the socio-political circumstances, including health, that defines the life journey of most Aboriginal people.

Currently in Australia there are three sites where research is being conducted that is exploring what a new model of community governance might look like.

These communities are the Gunditjmara people in Victoria, the Ngarrindjeri nation in South Australia and groups and individuals from the Wiradjuri nation in NSW.

The Australian research is based on the Harvard Project wherein researchers work in partnership with First Nation communities in the USA to explore new models of Indigenous governance and economic development. The research from that project tells us that:

Sovereignty matters. When Aboriginal nations make their own decisions about what development approaches to take, they consistently out-perform external decision makers on matters as diverse as governmental form, natural resource management, economic development, health care, and social service provision.

Institutions matter. For development to take hold, capable institutions of governance must back the assertions of sovereignty. Nations do this as they adopt stable decision-making rules, establish fair and independent mechanisms for dispute resolution, and separate politics from day-to-day business and program management.

Culture matters. Successful economies stand on the shoulders of legitimate, culturally grounded institutions of self-government. Indigenous societies are diverse; each nation must equip itself with a governing structure, economic system, policies, and procedures that fit its own contemporary culture.

Leadership matters. Nation building requires leaders who introduce new knowledge and experiences, challenge assumptions, and propose change. Such leaders, whether elected, community, or spiritual, convince people that things can be different and inspire them to take action.

The research emanating from the Harvard Project indicates that there is an obvious and urgent need to shift paradigms if real and sustainable traction and meaningful outcomes are to be achieved in Aboriginal health, poor education experiences and learning outcomes, disproportionate incarceration rates, poverty and spiritual fatigue.

If long overdue and sustainable change is to occur it will require the design and adoption of a new model of engagement, one that empowers local communities so that Aboriginal people are in greater control of their lives and how best to address their needs and aspirations.

Health systems in NSW, and equivalent bodies in other health jurisdictions, must work with local Aboriginal communities to negotiate an Aboriginal Health and Wellness Accord, which is underpinned by a set of clearly defined and community endorsed principles and strategies that are designed to, implement, monitor and continuously evaluate progress against agreed local Aboriginal health and other social justice targets.

There is no ‘one size fits all’ solution to address the long-denied rights and freedoms of Aboriginal people, including health inequality and the right to live free of poverty, racism and discrimination, and with dignity.

Even in the face of brutal indifference and pathological racism, not to mention the intransigence that defines the political and societal treatment of our uniqueness as the First Australians, Aboriginal people have survived.

Change and transformation in the health status of Aboriginal people requires a shift in policy and programming and in the hearts of power. A shift that creates empowering involvement of Aboriginal peoples through negotiated partnerships between health and other service providers and members of Aboriginal communities.